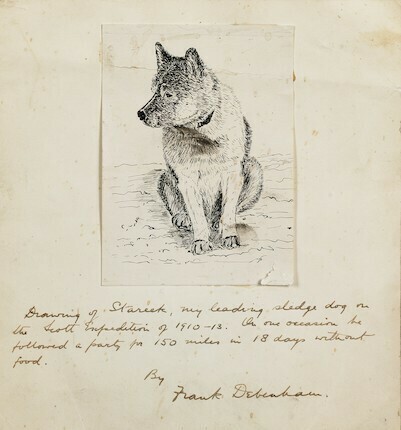

One of our lovely clients Doug edited a book some years ago about polar explorers which is called “Antarctica – First Impressions 1773-1930”. He has recently drawn our attention to a chapter in this book about a polar dog called Stareek. Stareek means ‘Old Man’ and he was one of the sled dogs on Captain Robert Scott’s final fatal journey to the South Pole. Stareek’s life has been described by fellow polar explorer and geographer Frank Debenham. With Doug’s permission, we have copied the chapter about Stareek to this post, so if you would like to learn about Stareek’s eventful life, please read on!

This story is written for the purpose of commemorating a few of the deeds of a dog called “Stareek”, who, like so many other dogs, just did his best and died, but who in wisdom, endurance and even lovableness rose above his peers in the dog teams which accompanied Captain Robert Scott on his final fatal journey to the South Pole.

Stareek was rather older than most of the others and was a leader … his name means “Old Man” and I firmly believe that even when a puppy he had the look of age and wisdom and that his original master named him Stareek for this reason.

Stareek led his team throughout the depot-laying journeys of the first Fall and won praise from his driver. Always quieter than the other dogs, he was not remarkable in any particular way during the Winter for he did not go seal hunting on the ice and get drifted off to the open sea, to death by starvation, nor did he break his teeth levering at seal carcasses frozen like a board.

Stareek began the great journey to the South Pole in the Spring, fit enough but with his age against him. The stern slogging over the variable surface of the Barrier, now glass hard, now soft and clogging, proved too much for him. The dog teams had done three hundred miles of this and had another hundred to do before their turn came to go back, when two of the older dogs showed signs of the strain and were failing fast. These two were Stareek and Tsigane. On a more desperate journey their fate would have been swift death, and the other dogs would have had a meal of fresh meat. But this journey was not yet desperate and, as two men were to return from this point pulling their own sledge, Captain Scott said they could take the two dogs with them on the bare chance of saving them, though no dog food could be spared, and the men would have to share their own rations with the dogs.

The men, glad of the companionship and full sympathy for the dogs, took them and started back. Tisgane at once approved of this turn in his affairs, but Stareek did not, and after sundry chasings to bring him back from following the Poleward party he had to be tied to the sledge and hauled along by main force. That night Stareek gnawed through his lashings and started back to rejoin his team and in the morning the men, sorry enough to lose him, could do no more than give him up to his fate.

So they sledged away northward, a weary journey for two men alone and lavished care and biscuit fragments on Tsigane, who even had a soft bed made up for him on the sledge every night.

Eighteen days after Stareek’s desertion they pitched camp about 200 miles from where they had left the Pole party. They had a disturbed night, because Tsigane kept barking and moving about quite contary to his habit. In the morning when the men looked out of the tent they saw the reason for Tsigane’s unrest: on the sledge, in Tsigane’s bed, was Stareek.

He was hardly recognizable and so weak that he was quite unable to walk and for some days was hauled on the sledge till biscuit fragments made him strong enough to carry himself.

Now consider what that dog had done. Stareek was a weak dog, unable to pull his full weight in the team and when he deserted the two men he had probably tracked his old team for at least twenty miles. Some instinct or dog-reasoning had told him that he would never catch them, so he turned North again and tracked the two men. For 200 miles and for eighteen days, without a shred of food, he tracked them and when, almost at his last gasp, he caught up, he still had enough authority left to turn Tsigane out of his comfortable bed.

That is a feat which should be preserved in the annals of travel and that is why I consider Stareek’s name and portrait should be placed on record. And my right to tell this story lies in the fact that I was his last master and driver and am very proud indeed of having had that honor.

The poor “old man” had a little longer to live and I am glad to say that he came to look upon me as a good friend however hopeless a driver and unbent to me as much as he ever did to anyone, so that I looked forward to giving him a peaceful year or two of life in civilization. But it was not to be, for three weeks before our ship arrived to take us home, he died suddenly from some obscure complaint. He lies now and forever under the frozen gravel of Cape Evans, beneath the shadow of Mount Erebus, the most southerly volcano in the world.

I think that if you read his story and study his portrait you will agree that here indeed was a dog of dogs, enduring beyond belief and worthy of a small niche in the temple of canine fame.

From Frank Debenham: World Wide Magazine. New York, 1933.