The frozen future of conservation

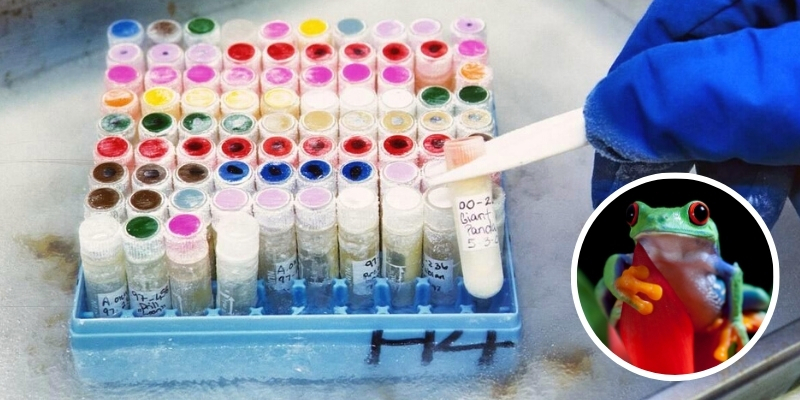

Ever heard of biobanking? It’s a method of collecting and storing biological samples for research. Often used for human data, the concept is now being implemented for the conservation of Australian wildlife. The Australian Frozen Zoo, based in Melbourne, is granting native, at-risk species a new chance at survival. By collecting living cells and genetic material, such as sperm, frozen zoos can combine biobanked material with assisted reproductive technology to revolutionise wildlife conservation. And at the top of the list at the Australian Frozen Zoo are amphibians.

In an article by SciTechDaily, Dr Simon Clulow, a senior researcher from the Department of Biological Sciences at Macquarie University, stressed that more than 200 amphibian species are currently in urgent need of conservation intervention, and over a further 700 need captive populations, however traditional captive breeding programs pose too many obstacles to be seen through for every species in need.

Captive breeding has had many success stories, such as the survival of the giant panda, but sadly, program maintenance is not easy.

Firstly, captive breeding is expensive. To maintain just one species in a captive breeding program can cost more than $200,000 a year. Unfortunately, the programs are already underfunded, and as each program needs to go on for several years or decades before its objectives can be achieved, many species won’t get their chance.

Secondly, there are complications with the effects captive breeding can have on animals. As generations adapt to the environments, captivity can domesticate the animal, altering their behaviour and ultimately hindering their ability to survive or reproduce in the wild.

But biobanking gives us hope.

Researchers say that freezing endangered species’ genetics not only dramatically reduces the amount of funding necessary, but it could also “provide a 25-fold increase in the number of species that could be conserved.”

Bringing biobanking into captive breeding could also restore 90% of the original captive population’s genetic diversity for 100 years! This crosses out problems associated with colony size and inbreeding, while providing an opportunity to not only conserve the so-called ‘charismatic megafauna’, but the ecosystems that are dependent on their survival as well.

So far, the conservation community are yet to seize the full potential of frozen zoos, but with the evident large-scale benefits that biobanking offers to wildlife sustainability – as disease, a changing climate and habitat loss continue to threaten species around the globe – this innovative method of conservation surely can’t be given the “cold” shoulder for long.